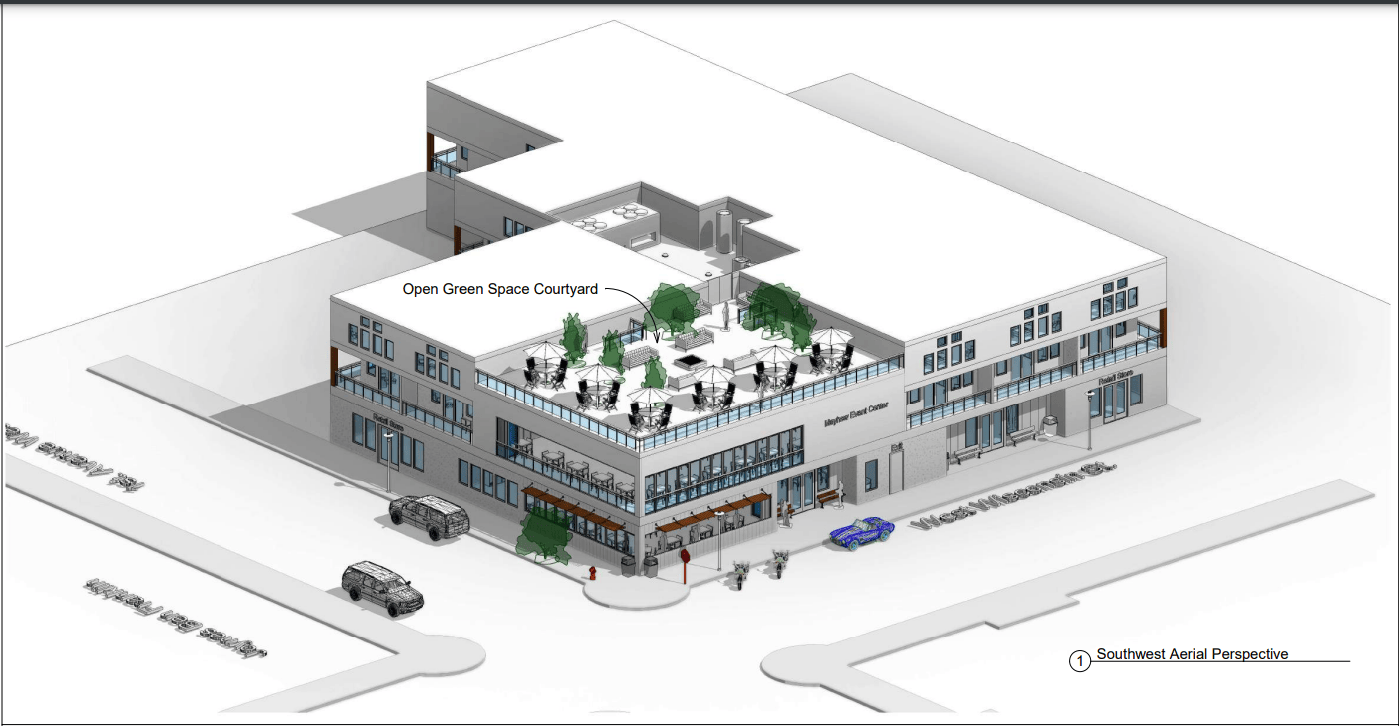

New development planned for Grand Marais downtown on site of 3 businesses previously destroyed by fire

January 4, 2024

Postal workers rally in Minneapolis against 'senseless crimes' targeting mail carriers

January 8, 2024Long before he was a state lawmaker, Rick Hansen worked for the Minnesota Department of Agriculture, helping develop best practices for managing nitrogen fertilizer.

Three decades later, Hansen, a DFL representative from South St. Paul, says the state’s approach to preventing nitrogen pollution hasn’t worked.

Hansen, chair of the House environment committee, thinks the state should raise its fees on fertilizer, the source of the majority of nitrate in southeast Minnesota waters.

“We have tried incentives. We’ve tried education. We’ve tried voluntary management practices,” Hansen said. “We’ve had meetings after meetings … and the nitrogen fertilizer use continues to go up.”

Hansen’s proposal comes amid increased scrutiny of the role cropland agriculture plays in nitrate pollution.

Southeast Minnesota is particularly vulnerable to nitrate contamination because of its karst geology, which allows pollutants to travel easily from the surface to the groundwater. In some townships, 40 percent of private wells tested had nitrate levels higher than the safe health limit.

Consuming too much nitrate can pose health risks, including a rare but sometimes fatal condition in infants known as blue baby syndrome.

In November, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency told state agencies to take additional steps to address nitrate contamination in southeast Minnesota, including providing safe drinking water immediately to residents with contaminated wells.

Raising fertilizer fees could partially fund actions to help those people affected, Hansen said.

“It’s not their fault that the water is contaminated,” he said. “They’re going to need safe drinking water. And how do you pay for that? It should not come from the general taxpayer. It should come from those responsible.”

Hansen’s proposal likely will meet with pushback. Last year, the state agriculture department proposed raising the inspection fee on fertilizer from 39 cents to 64 cents per ton. The agency said the cost to the average farm would have been about $20 a year.

But it failed after farm groups opposed it, and Republicans questioned raising fees amid a huge budget surplus. Minnesota Agriculture Commissioner Thom Petersen said with fertilizer prices skyrocketing, the idea didn’t get much support.

“For a lot of farmers, it just feels like piling on,” he said.

Petersen did get legislative authority to raise the inspection fee incrementally by 5 cents a ton starting Jan. 1. This year, farmers will pay fees totaling $1.16 per ton of fertilizer. Some of the revenue pays for inspections and permitting; some for fertilizer research at the University of Minnesota.

Petersen said he doesn’t think a fee increase is likely to get more support this year. He said there’s a question of what the additional revenue would pay for.

“Raising the fee — if it’s not done with the work that we need to do and targeted, it’s not going to clean up anything faster,” he said.

One group opposed to a fee hike is the Minnesota Milk Producers Association. Executive Director Lucas Sjostrom said much of the nitrate in groundwater dates back to farmers decades ago.

Today’s farmers are better using — but not overusing — fertilizer to produce better yields, he said.

“We can’t penalize those who were there decades and decades before us,” Sjostrom said. “It’s a slow problem to solve. It’s just going to take time.”

Dan Glessing, president of the Minnesota Farm Bureau, said GPS and other technology is helping farmers apply fertilizer to their crops with more precision.

“We know exactly what that crop is taking out each year,” he said. “We’re spoon-feeding that crop now, where we never used to do that.”

Glessing said the Farm Bureau does support the Agricultural Fertilizer Research and Education Council, a farmer-led research program funded by a 40-cent-per-ton fertilizer fee. But he said the bureau doesn’t think any additional fertilizer “tax” is necessary.

Even some environmental groups aren't convinced raising fees will do much to solve the nitrate problem.

“Broadly speaking, we’re of the mind that industry should be held accountable for recovering some of the social costs of pollutants,” said Trevor Russell, water program director with the nonprofit Friends of the Mississippi River.

However, if the additional fee revenue is used to continue the same strategies, it'‘ not likely to succeed, Russell added.

“We’ve spent billions and billions on trying to incentivize the best on-farm practices,” he said. “If that were going to work alone, it probably would have worked by now.”

While farmers have gotten more precise in how they use nitrogen fertilizer, Russell said they still routinely overapply it — by as much as 100,000 tons per year in Minnesota, according to a 2018 estimate.

He thinks it might make sense to charge a tiered fee — one for applying fertilizer at recommended rates and a higher one for any excess, creating a financial incentive for farmers to reduce their overall fertilizer use.

“The individuals that are most responsible for over application are most financially responsible for the consequences,” Russell said.

There are likely to be other proposals at the state Capitol to deal with the nitrate issue. One idea Hansen suggests is using conservation easements to take farmland in wellhead protection areas, where public drinking water is drawn from, out of production.

“A big problem is going to is going to require a variety of solutions,” he said.

Sen. Aric Putnam, DFL-St. Cloud, who chairs the Senate agriculture committee, said he plans to hold a hearing on water quality issues this session.

Putnam said while he believes that “polluters should always pay,” he doesn’t believe most farmers overfertilize, because it’s expensive, and because they care about clean water.

“Every farmer knows that healthy soil and water increases their yields,” Putnam said. “It’s in their own self interest to have healthy soil and water. So they just want help to be able to do it better.”