Tesla cuts its car prices around the world after week of turmoil for the company

April 22, 2024

Why do so many couples fight about money?

April 22, 2024At Integrated Recycling Technologies in St. Cloud, every discarded electronics gadget is a potential gold mine.

Huge cardboard boxes are filled with discarded cell phones, circuit boards and other devices.

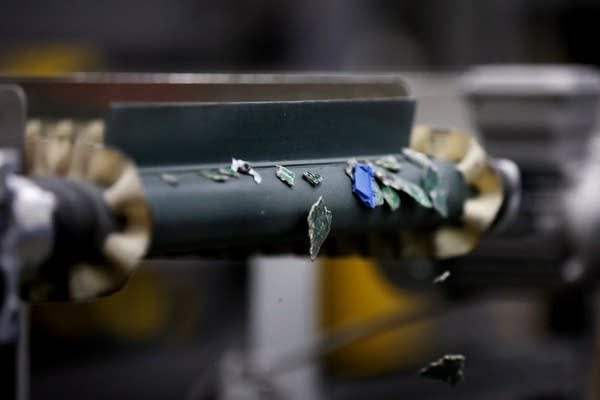

“We take a laptop or a desktop, cell phone — anything that has a circuit board in it — and we’ll shred it,” said Dave Owens, chief operations officer, during a recent tour.

A magnet pulls out the steel, and an electrical current removes the aluminum. An optical sorting machine removes bits of plastic by color. The rest is incinerated, ground up and melted with lead to pull out the precious metals and other valuable materials, including gold, silver, copper, platinum and palladium.

IRT, the state’s largest e-waste recycler, processes about 37 million pounds of e-waste a year from both businesses and individual residents. But Owens says they could do even more — and increase from 87 employees to about 200 — if more people recycled their unwanted electronics.

The 240,000-square-foot St. Cloud facility was built to process up to 150 million pounds of electronics a year, Owens said. In comparison, Minnesota generates about 133 million pounds of e-waste Minnesota generates annually.

“We could process everything that the state generates right now,” he said.

A bill being debated at the state Capitol could boost IRT and other recyclers. It would update Minnesota's current electronics waste law, which was passed back in 2007 — the year the first iPhone was released — and focuses mainly on televisions and computers.

The bill would cover 100 percent of electronic waste, and make recycling electronics free for all Minnesotans. To fund the program, it would add a 3.2 percent retail fee on most electronic items when they are sold. Cell phones would have a flat 90-cent fee.

The bill’s author, state Rep. Athena Hollins, said the current fees most Minnesotans must pay to recycle old computers or printers can be a deterrent.

“We know when people show up to a recycling place and they find out they have to pay to recycle it, a lot of them just turn around and dump it into their regular trash feed," said Hollins, DFL-St. Paul.

Electronics thrown in the garbage end up in landfills or incinerators, where they cause a lot of problems. Some contain lead and other toxic materials that can pollute the air and groundwater. Lithium-ion batteries found in many electronic devices have sparked fires.

Electronics make up 2 percent of the total material going into landfills, said Maria Jensen, co-director of Recycling Electronics for Climate Action.

“If you can reduce the total amount going into our landfills by 2 percent, that’s going to extend the life of our landfills,” Jensen said. That would likely save millions or billions of dollars in costly landfill expansions and operations, she said.

Supporters of the bill also argue that recovering precious metals and other materials from old electronics is critical, as Minnesota and the nation transition to a clean energy future.

“All of the things that we’re making, like solar panels, are going to need those precious metals that are in our phones,” Hollins said. “And right now they’re sitting at the bottom of landfills, just wasted.”

Recycling electronics properly also helps protect people from data breaches and identity theft, Owens said. At IRT, workers wipe cell phones and hard drives clean before they're resold or destroyed.

The 3.2-percent retail fee would give consumers peace of mind to know their electronic product is going to be handled responsibly at the end of its life, he said.

“When you bring it to a facility like this, you don’t have to worry about that anymore,” Owens said. “It’s being taken care of correctly.”

The bill has had hearings in the House, but has stalled in the Senate. Some legislators and business groups object to adding a new fee that could be passed onto consumers.

Hollins said the fee would actually be less than what most people currently pay to recycle their electronics, which can be as much as $25 for a $100 printer. The retailer fee on that same printer would be about $3, she said.

“The cost is on the front end as opposed to on the back end,” Hollins said.

While it may not become law this year, the bill’s supporters hope to keep the conversation going about how to tackle the growing e-waste problem, and how Minnesota can do a better job of mining electronics for their critical components.

“Hopefully, people can see the real value that's there, and figure out a working solution that will bring more of these electronics to our recyclers,” Hollins said.